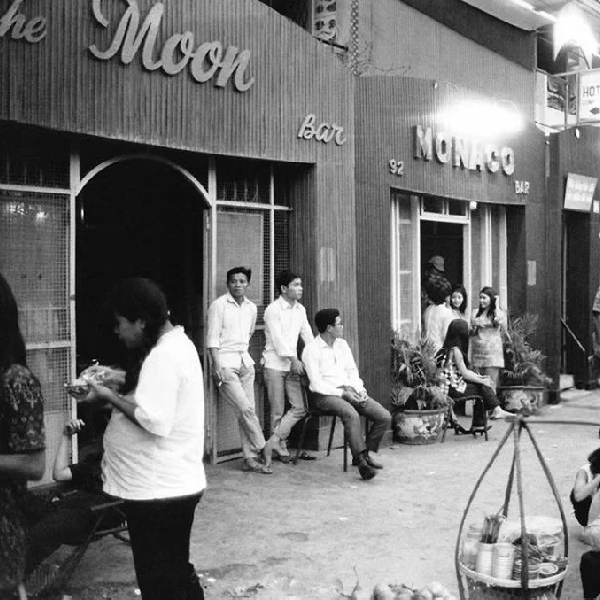

The novel Mole Creek starts in the semi-mythical area of wartime Saigon which was effectively a no-go area for white American soldiers. It’s there that one of the central characters of the novel is compromised by a Russian spy, something that reverbs to modern-day Australia half a century later.

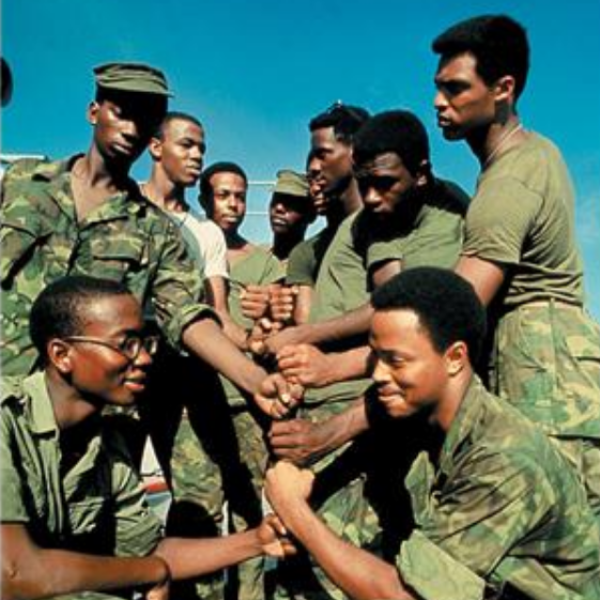

That there were Russians operating undercover in South Vietnam is a matter of informed conjecture. That there was such an area where African-American soldiers could escape from their racist comrades, and enjoy their music, food and less legitimate pleasures, is a matter of historical fact, as James Dunbar discovered when researching the book.